How to Write a Song

In 5 Easy Steps

It all starts with a song

The entire music industry is based on the concept that people like to hear songs. Where that started, no one can say. Perhaps our earliest ancestors found pleasure in simple percussion rhythms or sounds blowing over resonant spaces. Maybe they sought to duplicate these and control them, rearranging their discoveries into repeatable form.

It might have started with a voice, with the realization that it could be modulated and controlled and, again, these vocalizations could be repeated, performed for others and made pleasing with time and practice.

Origins of Song

The idea of the song likely progressed organically. It starts at the end of silence and ends with a return to silence. Complexity grew. Simple beats and melodies became overlaid, varied, passed to others across distance and time, and these proto songs took their place in the culture of their creators, adding meaning to life beyond the functions of survival.

The “steps” mentioned in the title are perhaps overstated in importance precisely because of the complexities involved in writing a song. There’s no single way to write a song. The process is craft wrapped in mystery, sprinkled with inspiration and growing into a piece of work that’s perhaps molded by its composer before transcending its origins to become a piece of our contemporary folklore.

The Impossibility of Process

If one of the chief composers of The Beatles doesn’t really know how to write a song, you might wonder about your chances of doing it, but when you flip that logic it starts to reveal the beauty of the songwriting process. If Paul McCartney doesn’t need to know how to write songs, then neither do you.

Rules? We don’t need no stinkin’ rules

So, when you look at these 5 steps, remember that their order has a logic that’s arbitrary. You don’t have to follow that order. This is not a recipe, though you could use it as such. We’re discussing songwriting in a popular music context, and so much of what is covered here refers back to that, but there’s no reason you can’t adopt, adapt or ignore any of these steps in any genre of music.

If there’s one guiding rule about songwriting, it’s that there are no rules for the process of composition. It’s music, so there are rules aplenty about melody, harmony, sounds that work and sounds that don’t. It’s a business, which dictates style, form and salability. Ultimately, though, it’s an art, and the creation of art is, at its core, about freedom to choose from all that’s gone before and from what you may sense of the future.

So, read on and consider these steps as advice, not gospel truth. If you pick up an instrument or hum out a melody after reading, then this article is a success, whether you follow this process or not. It’s accomplished the first step, arguably the most important one in songwriting.

Step #1: Inspiration

Paul McCartney’s song “Yesterday,” thought to be the most recorded song in history, began as a melody in a dream. “We’ve Only Just Begun,” the 1971 hit for The Carpenters, started life as a jingle for a bank. Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” traces back to a deodorant that was marketed for high school-aged girls.

“Smoke on the Water” told the tale of a real-life of a casino fire that started during a Frank Zappa show. Mark Knopfler overheard appliance store workers commenting on music videos playing in the store, and “Money for Nothing” was born. Knopfler also penned the beautiful “Sailing to Philadelphia,” which re-told the story of English surveyors Charlie Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, whose names live on as the Mason-Dixon Line, the metaphorical and literal divider between the North and the South in Civil War-era America.

Varied sources

Inspiration can grow from a snippet of conversation that then becomes a title or a lyric. A melodic phrase may repeat over and over in your mind until you’re compelled to shape it into a song. Perhaps you develop a riff on an instrument and it, too, demands expansion. The Rolling Stones built a career (and some of their biggest hits) around just this strategy.

Change it up

When your songwriting gets stale, look to new places for inspiration. Keep a notebook to record words and phrases that catch your ear and imagination. If you usually write the lyrics first, try making a melody first instead. Take an existing song that you like and try to mimic its elements without using those elements. Write new lyrics for the existing song. Write a new melody for the existing lyrics.

The pool of inspiration is vast, and once you tune into the ideas that resonate with you, you’ll likely find that these sources become more frequent. As your body of work grows, you may identify places you haven’t gone before and get ideas that fit “in between” your previous inspirations. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter where the inspiration comes from or even if the idea is recognizable in your finished work.

Think of inspiration like the turning of a key in the car’s ignition. Once it’s started, you can forget about it and just go for a drive. Songwriting, like travel, is often about the journey. The destination may be important, but what you learn along the way counts.

Step #2: Chords and Melody

12-bar Blues Chords

Anyone with passing knowledge of an instrument or musical theory likely knows about 12-bar blues structure, or I IV V (one four five) chord relationships. Many, many popular songs can be reproduced using only three chords. Add one more chord, the minor sixth, or vi, and you have the framework around which much of popular music is built, from the post-World War II era to today.

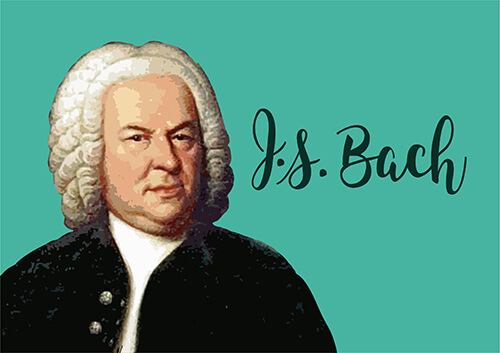

For those who need a deeper explanation, the Roman numeral chord designations permit an understanding of chord arrangements regardless of what key a song is in. Western music uses 8 major note divisions in its scale with four more smaller divisions falling in between.

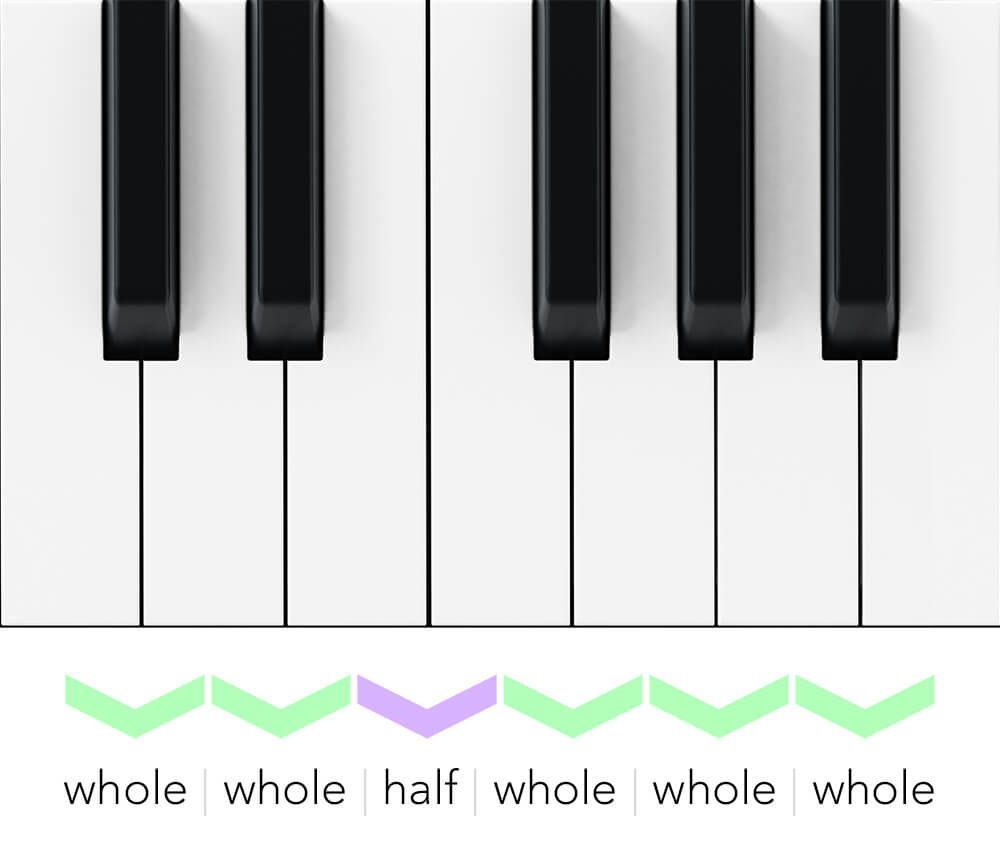

The C Major scale uses the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C to make up an octave, and the pattern repeats above and below. A G Major scale uses G, A, B, C, D, E, F# and G. The major scale takes the 12 smaller divisions and arranges them into a pattern of half steps (one note division) and whole steps (two note divisions).

The pattern for a major scale is:

If you’re familiar with a piano keyboard, start at a C on the middle of the keyboard and follow that pattern up and you’ll see how white and black keys combine to make those relationships. For other keys, notes are bumped up or down to keep the step pattern and sharps and flats are used in those cases, like the F# in the key of G.

While the letter names of the notes change, the step relationships do not. This characteristic lets the Roman numeral system work, but with a nod to chords.

Roman numeral scales look like this:

I ii iii IV V vi vii0

The upper and lower case of the numerals represent major and minor chords that work naturally with the major scale. The superscript 0 represents a diminished chord, which have a discordant sound and tend not be used frequently in popular music.

So, for C, the natural chords are:

C major, D minor, E minor, F, G, A minor, B diminished

Note that the Roman numeral system has no eighth degree, it simply starts again with I, since octave considerations aren’t needed as much in chord relationships.

You’ll see that, in any major scale, the I IV and V chords are the natural major chords for that scale. Adding the vi chord creates perhaps the most-used chord grouping in all Western popular music. In the key of C, these chords would be C, F, G and A minor. Change the key to G and the big four chords are G, C, D and E minor.

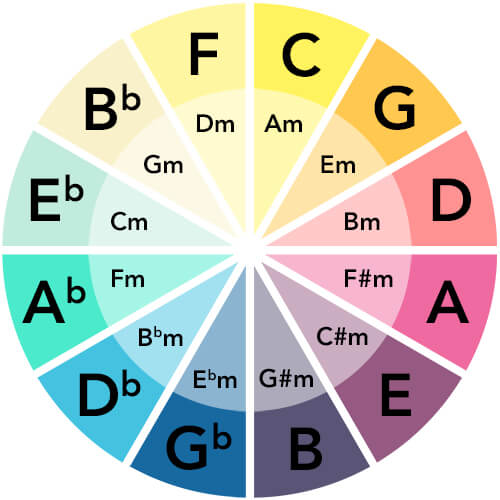

The Circle of Fifths

There are plenty of resources online that expand on the power of the circle of fifths, so check it out when you’re looking for the lost chords that don’t fall into the I IV V vi progression.

Melodies over Chords

Changing keys typically allows you to adapt a chord progression to a range that suits your voice. Why is that important? While there’s nothing that says it must be done that way, melodies are often developed vocally over a simple chord performance. Strumming chords on a guitar or playing triads on a piano gives both rhythm and a harmonic basis upon which to either create a melody or fit words into a song.

Even with electronic music creation, chords create a foundation over which lyrics, raps or melodies can grow. With a beat and a chord progression, your idea starts to become a song. However, there’s still lots of work to be done.

Step #3: Lyrics

Setting the stage

Your inspiration may come from a lyrical basis. Say, for example, the phrase “crickets and airplanes” catches your attention. It doesn’t matter why, you just decide the phrase sounds song worthy, and you recorded it in your notebook. Where do you take this phrase? Well, that’s the start of a zillion tiny decisions that you need to make to write a song.

Let’s say you think “outdoors” when you consider the phrase. What happens outdoors? Weather, maybe? Sunny days, rainy days and so on. You’re taking your original phrase and trying to do two things:

• Creating mental pictures, and

• Developing some sort of narrative

You want to nudge your audience around, to see things as you see them. This process is imperfect, and some of the best songs ever written mean something different to every listener. However, it starts with your vision, your choices and your ideas.

So, the phrase develops into:

Crickets and airplanes

Sunshine and cold rain

The setting is now outside, but open to interpretation. If you live in Florida, say, and you went to the beach, you may think about the beautiful day and the alligator in the sun you drove by along the way. There’s an idea from your real life that you want to add into the texture of your mental picture.

Now the lyric becomes:

Crickets and airplanes

Sunshine and cold rain

Gators at the side of the road²

Think about the images these words have for you. Everyone reading them will have a slightly different idea in their minds. You’ve set the stage for a story.

²“Crickets and Airplanes” © 2020 Jennifer Elliott and Scott Shpak. All Rights Reserved

Developing a verse

Your initial phrase is now a short verse. You may not yet know where the narrative is going, but you have a few things established that will help you progress. The first item is syllable count. These can serve as an aid for feeling rhythm or cadence inherent in the lyric. With two lines of five syllables and one line of eight, there’s now the basis for a rhythm.

Try speaking the words to find an emphasis on syllables that you’re comfortable with.

You might come up with something like:

duh-DAH duh DAH-duh

duh-DAH duh DAH duh

duh-DAH duh duh DAH DAH DAH DAH

This is both the start of the musical rhythm of your song and the template for subsequent verses. You might take the day at the beach idea and expand on it for your narrative, or you might pursue the outdoors idea. You could throw in a character whose girlfriend just dumped him or make it about a couple on a Sunday drive. It’s very powerful, being a songwriter.

Whatever narrative idea you develop, your subsequent verse ideas need to echo the syllable structure in both count and emphasis. There’s one other aspect the first verse gives you.

Rhyme time

“Airplanes” and “cold rains” are internal rhymes. That is, the rhyme scheme resolves within the verse. “Gators at the side of the road” leaves the word “road” hanging as an obvious external rhyme, a way of tying verse number two with number one. Clever rhymes can be a hook that serves as the song’s focus. It’s also possible to abandon rhyme altogether.

If you can’t imagine that, consider the song “Need You Tonight” by INXS. Apart from a match in the first verse of “yesterday” and “that’s okay” there’s not a rhyme to be found. When it comes to syllable counting and rhyming, you start to run into rules that can be broken in favor of a strong idea. To rhyme or not to rhyme is up to you.

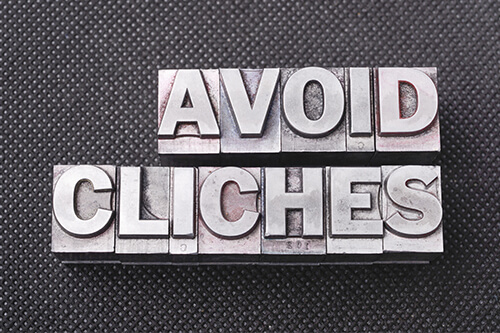

Cliché killer

If a character in your song gets down on his knees and begs someone please, just shoot him and free him from his misery, before he spreads it to others, taking your reputation as a songwriter with him.

Avoiding or twisting a cliché can be a satisfying moment of creativity that catches attention and builds depth into your song.

Consider:

Two’s company but three’s a crowd

Ugh, overused and it has poor syllable structure too. However, twist it with a bit on non-linear logic and it becomes:

Two incorporate but three’s a crowd³

It’s added a twist that makes a listener think, but not too hard. It’s these twists and turns that give songs identity, and it’s your job as a songwriter to seek out your own nudges around the overused and mundane language of popular song. It’s not always easy, but it’s always worth the effort.

³ “Your World” © 2004 Scott Shpak. All Rights Reserved

Step #4: Structure

Like chords, there are certain patterns that crop up often, and you can borrow from these liberally, since they will present your original ideas in a way that’s accessible to others.

Knowing your ABCs

The most common structure or form in popular music again comes from the blues. The 12-bar blues progression describes both the pattern’s form and, indirectly, implies the I IV V chord sequence. When fleshed out to a song-length work, the 12-bar blues is most often arranged in repeated AAA song form. “A” in this case stands for the first subsection of the song, the A part. The 12-bar form at its most basic simply repeats the same 12 bar pattern again and again, until the song ends. There’s often a common refrain within the A part, usually a repeated last line. This easy repetition makes the 12-bar blues the choice for jamming musicians, since there’s no complex structure to remember.

Broadway show tunes frequently display ABAC structure. You can think of this as verse, pre-chorus, verse, chorus, for example. Three sets of quickly alternating song parts keep interest and typically make for a feeling of “completeness.” Over the course of a three-minute song (3:30 is generally regarded as the “perfect” length of a commercially viable song), that gives the listener three different themes.

The rock era typically followed this three section idea, though often in an expanded form such as AABABCBB, where A represents a verse, B is the chorus and C denotes a bridge that can often be very contrasting, and is usually played just once, while other parts have greater repetition. Many of the songs in the contemporary charts revert to simple forms, such as ABAB or AAAA, with instrumentation and production adding variety and keeping listeners interested.

The form for you

How do you decide the right form for your songs? Sometimes, it’s instinctively by feel. As you play, you begin to sense when it’s time to move to the next part. Other times, you may have written a great verse, but form tells you that another part is appropriate for the style of song you’re composing, so you break out the circle of fifths and keep writing.

While styles often dictate form, the structure of a song is yours to choose. There’s a reason why the old standby forms work, and there’s no shame in choosing a well-worn pattern, but it’s also another of those rules you can break, when it’s right for the song.

A side note about breaking rules:

Breaking rules for the sake of breaking rules doesn’t usually produce musical results. The best rule-breaking happens when the exceptions come naturally, such as finding the right chord doesn’t fit neatly into the circle of fifths, or when your 12-bar blues counts out to 14 bars. It can be done, as bands like Rush and Yes have demonstrated, but rule-breaking as a compositional musical hook depends on confident musicianship. Work closely to existing songs, styles and forms until you understand the rules that you’re discarding.

Step #5: Arrangement

The arrangement of a song differs from structure, though sometimes the ideas may be used interchangeably. Considering arrangement requires an idea for a song’s performance. For instance, if you’re writing a sensitive singer-songwriter piece, but you’re playing in a thrash metal band, you may not be able to join up song with performance. Many songwriters widely cross genres when they’re composing, and not every song fits in every genre.

Arrangement considerations may be optional. In the glory days of Tin Pan Alley, the songwriter composed and perhaps made a simple demo, then the Artist and Repertoire (A&R) man or the producer would worry about matching the song to artist and arranging it in an appropriate way.

Dance music is all about the beat, for example, and it’s the beat that drives all other considerations. Working on a home computer to build your beats, you’re already on a recording platform, so building up your composition over a sequenced drumbeat makes perfect sense. You can build your song structure at the same time as your beats, without thought yet for lyrics or music. This track-by-track assembly process is a terrific way to write songs with a trial and error aspect that lets you hear your thoughts as you compose.

With the same equipment, a guitar and voice performance of your song may serve as the basis of your arrangement. You can keep it simple or add more instruments to fill spaces or enrich the track. Even the decision to keep a song in basic form is an arrangement choice. If you’re devoted to your thrash metal band, then you’ll work toward the instrumental lineup of your group.

Wrapping it up

You can see, through this list of 5 steps, that any given song can originate from any aspect of that song. Step #1, Inspiration, can combine with any of the remaining steps as your song’s point of origin. Like Paul McCartney, you can ignore all the steps and just let it happen. It’s worked out pretty well for him.

Heck, if you’re a diarist, go back over your entries and you may find reams of inspiration. Poets, writers, painters, photographers and sculptors all turn to their powers of observation to create their art. Your task as a songwriter is to hone these powers to serve your vision, whether you’re writing about the world around you or the world inside your heart.

It’s what you bring to the songs you write that defines your art. There’s no right or wrong way to do it. With the software tools available today, you don’t even need to play an instrument to indulge your craft. It’s about desire and commitment. Everything else is details; challenges to overcome, learning curves to climb and successes to be had. If you want to write songs, you can do it, as long as that inner flame still burns.