What is the

Circle of Fifths?

Getting the most from your music

with an easy reference point

Perhaps the most useful bit of music theory for sight readers and by-ear musicians is a nifty little device called the Circle of Fifths. Essentially a graph of musical relationships based on the Western scale, the Circle of Fifths holds a vast wealth of shorthand knowledge that’s accessible to the most fundamental musicians, while offering enough depth to remain a useful resource for advanced players.

Understanding the Circle of Fifths does require a very basic understanding of music theory. You should know, for example, that the notes of Western music are A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, and that they repeat, forming octaves. Therefore, another A follows G, but is a higher pitch, exactly twice the frequency of the previous A, working up the scale.

You’ll know what sharps and flats are. Sharps, denoted by the ♯ symbol, raise any given note by a semitone, the smallest musical division in Western music, and flats,♭, lower any note by the same degree. Any two adjacent piano keys form a semitone and moving one fret on a guitar is also a semitone.

Chords are collections of three or more notes in various harmonic relationships, of which major and minor chords are the most common. If you understand notes, sharps and flats, and chords, then you have enough knowledge to start using the Circle of Fifths today.

Keys to the Kingdom

The Circle of Fifths takes its name from a musical interval – the space between two notes – that’s five notes apart.

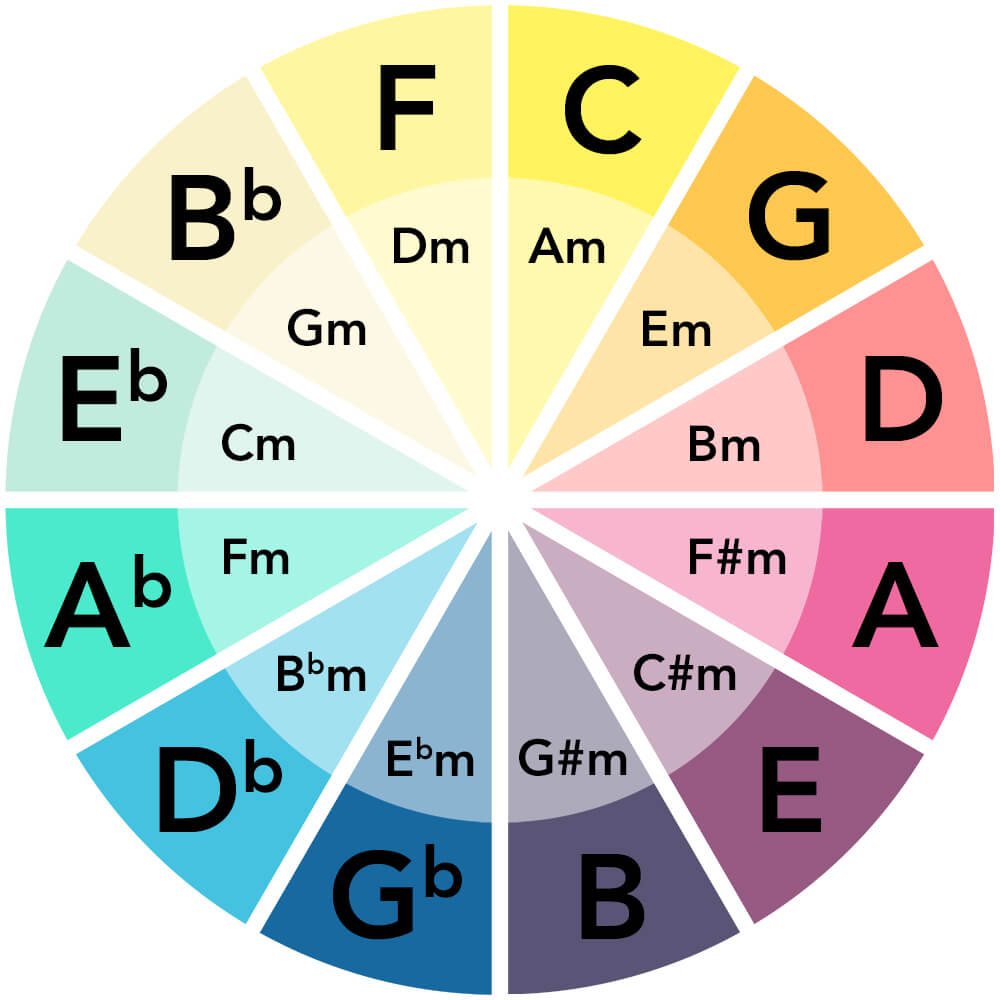

The circle uses, oddly enough, a circle, divided into 12 parts:

Every note in the scale can serve as the identifier, or tonic, of a key signature. Like chords, scales can be major or minor, with each type of scale having a unique relationship of intervals. If you know that a semitone is the smallest musical interval, it makes sense that a whole tone is the next largest interval. Semitones and whole tones are also known as minor second and major second intervals, to keep with the mathematical system used by fifths.

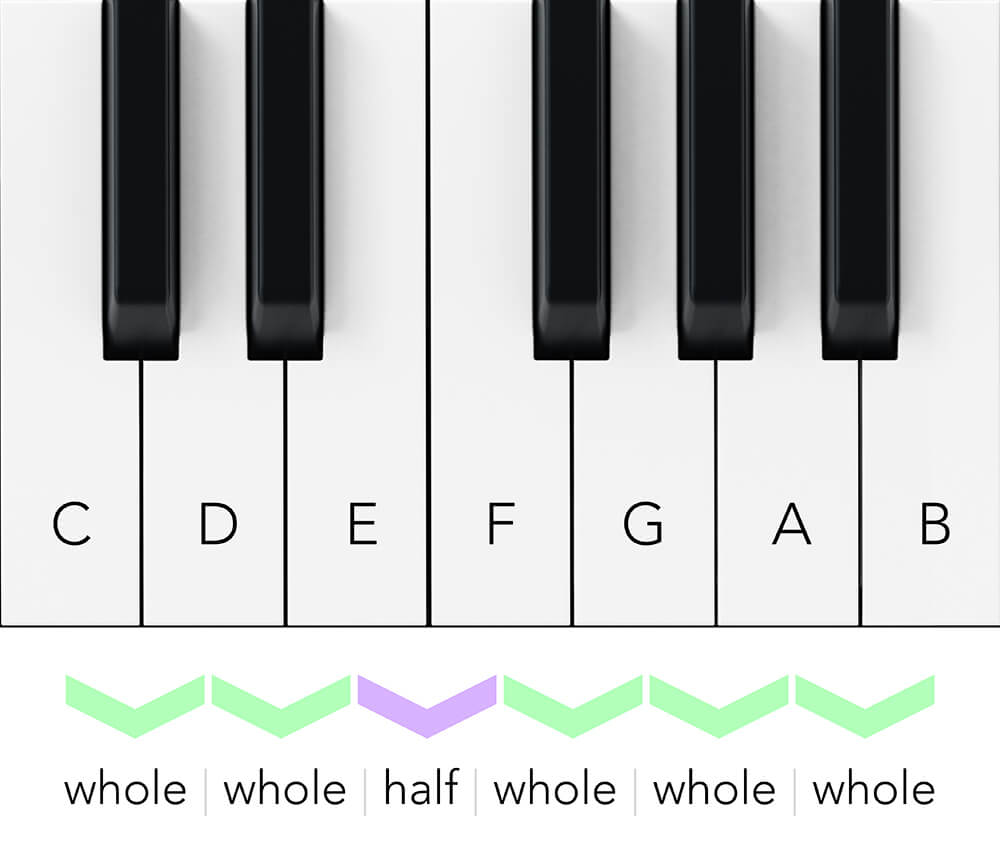

In the key of C, the pattern of the major scale plays entirely on the white keys of a standard musical keyboard. Therefore, the notes of the scale need no modifiers (sharps or flats) to create the pattern of a major scale.

The notes of the C Major scale are:

C, D, E, F, G, A, B

The interval pattern for a major scale follows the spacing of the white keys, so it goes:

Whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole

Now, since we’re working with the Circle of Fifths here, we can count five notes on the C Major scale (C being #1) to find that G is the fifth, relative to C.

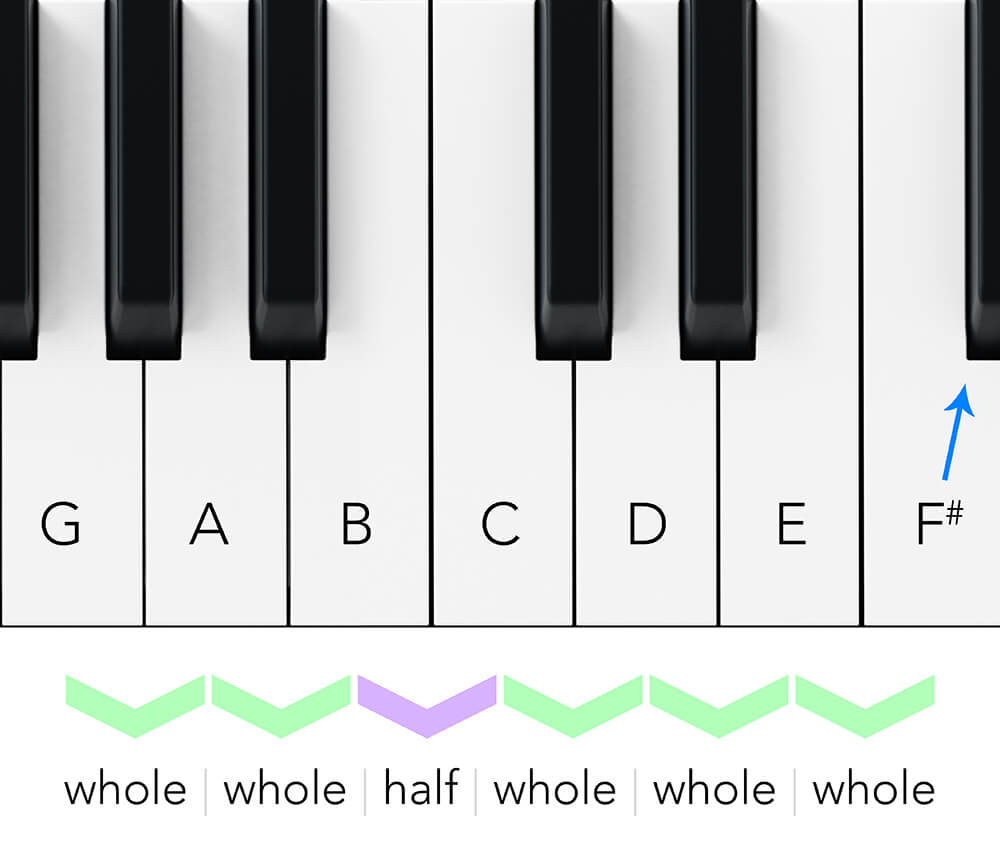

The notes of the G Major scale are:

G, A, B, C, D, E, F#

To maintain the interval pattern for the key of G, we need to bump the F up a semitone to F#. The first half step occurs naturally between B and C. For the second one, though, we must move off the white keys or the scale sounds wrong. That F# restores the major scale sound.

Counting five steps up on the G scale brings us to D. The same thing occurs, but now, as well as the F#, we must bump up the C to a C# to keep the major scale interval pattern. We can do this six times, jumping up a fifth with each step, moving from no sharps to six sharps, forming the keys of C, G, D, A, E, B, and F#.

The eagle-eyed will spot that notes like F and A Flat have no key signatures represented. That’s because instead of sharps, some keys need to lower notes to preserve the major interval pattern. It follows the same rules as with sharps, just moving down instead of up. Count down four steps to get to F, which needs one flat, B flat, to keep the major scale sound, then the fifth in F major becomes B flat, which needs two flats for its major sound, and so on, six times until we arrive at G flat. A quick glance at the keyboard shows that G flat and F sharp are the same black key. Therefore, G flat and F sharp are the same scales with the same notes, even though they have different names.

Laying out these relationships with sharps to the right and flats to the left give us the basis of the Circle of Fifths.

Why down four steps?

A scale has 7 notes, then begins again in the next octave. So, in the key of C Major, the fourth interval counts down starting at B, the last note of the scale. Moving clockwise around the Circle is always in fifths, while counterclockwise is always in fourths.

A Minor Detail

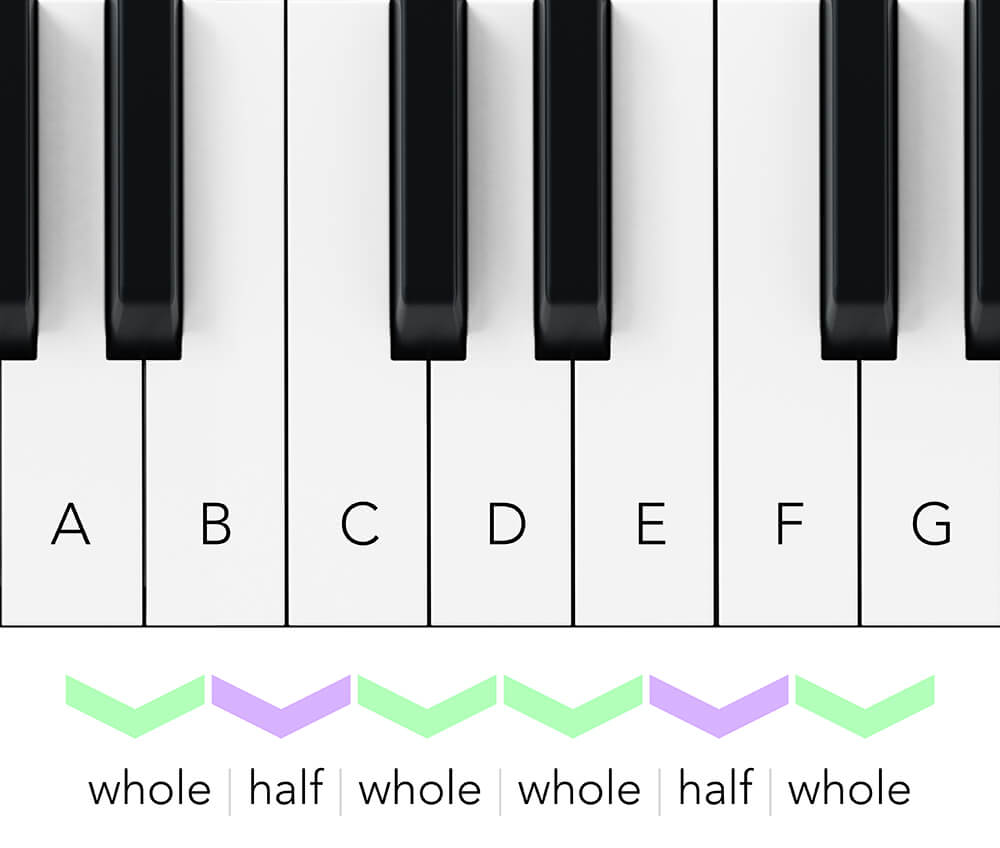

However, there’s one other thing we must consider, the Minor scales. As it happens, though, we’ve already done the legwork for Minor scales because every Major scale has a related Minor. Minor scales differ from major scales by the relationship of intervals.

Those look like this:

Whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole

If we look at the key of A Minor, the notes are:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G

In other words, the same as the notes in C Major, but with a different interval sequence. So, with all scales both major and minor and all key signatures laid out, a basic

Circle of Fifths looks like this:

You can find many variations of the Circle of Fifths, such as versions with guitar chord charts or information useful to other instruments, but any variation will start with this same layout and with the chords in the same position.

Using the Circle of Fifths

Because it’s a visual encapsulation for many of the mathematical relationships hidden in Western music, the Circle of Fifths can help with all sorts of musical tasks.

Learning key signatures

If you don’t have a Circle of Fifths wheel in front of you, you can rebuild it from the rules described above. Remember that C and A Minor go in the 12 o’clock position and that each step in a clockwise position is a fifth. That’s it. The rest is simply counting.

POWER TIP: This is perhaps the easiest way to commit the Circle of Fifths to memory. Take a pen and paper and draw it out for yourself. Start simply with all the chord names and their relative minors. As you learn more about the elements of the Circle of Fifths, start again, adding this additional detail. The act of thinking through the process and writing it down builds an intrinsic knowledge of the relationships.

Building chords

Finding the three notes of a basic chord, major or minor, becomes simple when you turn to your Circle of Fifths. Major chords build from specific scale intervals. These are the tonic, major third, and the fifth. The fifth is easy. It’s the adjacent note in the clockwise direction from the tonic. Start making a C chord and you know the fifth is G, since it’s next to the C on the Circle of Fifths.

There’s still the major third to figure out. Well, it happens to be conveniently located under the fifth, representing the relative minor chord, but for building purposes, we simply need the note name. Under G is E. Our C chord builds from C, G, and E. Of course, for convenient playing on a piano keyboard the third tucks in the middle, so it’s C, E, G, but as you learn more about chord voicings, the order of notes creates different sounds and musical impressions.

Use the same pattern to make any other major triad. E is E, G#, and B. F uses F, A, and C. D, F#, and A make up a D Major triad. Once you see the triangular pattern, every triad for every major chord becomes obvious.

Making minor chords works the same way, except there’s a different pattern. Look at the inner, minor chord ring of your Circle of Fifths. To make an A Minor chord, we start on A in the minor ring, at the 12 o’clock position, under C. First, we make a dyad with the fifth, the same as with a major chord, but staying on the minor chord ring. That gives us A and E.

The third in the case of a minor chord is a minor third. A minor third is an interval of 3 semitones, versus 4 semitones for a major third. With the Circle of Fifths, though, we don’t necessarily need to know that. We simply go to the outer ring to determine the third, the same clock position as the tonic, in this case C. Therefore, the components of an A minor chord are A, C, and E. Another triangle but starting on the minor chord ring.

POWER TIP: Use the minor shape to determine the notes for a C minor chord and compare it to the C Major chord we calculated earlier. The difference, an E flat rather than an E, defines the difference between major and minor versions of the C chord.

Chord progressions

The Circle of Fifths is standing by as a songwriter’s tool. As you know, the Circle of Fifths breaks down into 12 wedges. It’s simple to determine the chords that naturally work in a given key by choosing the wedge with its tonic. For an example, let’s use G.

To determine the complementary chords for the key of G, we look at the wedges on each side of G’s wedge. This gives us D in the clockwise direction and C in the counterclockwise direction. We know then that D is the fifth and C is the fourth, because of those directions of movement.

In the key of G, the chords G, C, and D work well together as major chords. Look at the minor chord ring and we see that E minor, the relative minor of G, works well with A minor and B minor. What’s more, any chord in either group can play nice with the other chords. So, you’ve just identified six chords that work well together.

Changing the example to the key of B flat gives B flat, E flat, and F as the majors and G minor, C minor, and D minor as the minors.

This is just the start of how you can use the Circle of Fifths for chord progressions, the baseline “rules” for chords. You can even use the Circle of Fifths to break these rules. Say you’re writing in the key of C and you need a chord to capture attention. Head directly across the circle and try chords that reside outside the “home” wedges.

Beyond the Circle

This article merely scratches the surface of the musical power of the Circle of Fifths. Once you’re adept at navigating, it becomes a tool that can help you transpose, modulate, predict chords, and understand the relationships built into the 12 chromatic tones of Western music.

Music theory can be a terrific sedative if you simply want to play. Theory and practice have that separation in many fields. If there’s one bit of musical theory that’s worth the effort to learn, it’s that of the Circle of Fifths because it’s a practical way to use the theory. It works for everyone, not simply those with a broad base in “serious” music.

All music is serious, a form of communication, and certain levels of fluency help you communicate. Think of the Circle of Fifths as a universal translator that helps you not only communicate with your audience, but with other musicians too. It’s also perhaps the most powerful influencer, after inspiration, to translate your musical thoughts into forms you can record, perform, and share.